As the crowd outside the jail grew to about thousand and daylight faded, the mayor and the police chief called the state adjutant general of the National Guard for help. Two officers and thirty-five enlisted men from the Tacoma company were assembled and dispatched to Centralia by special train.

As the crowd outside the jail grew to about thousand and daylight faded, the mayor and the police chief called the state adjutant general of the National Guard for help. Two officers and thirty-five enlisted men from the Tacoma company were assembled and dispatched to Centralia by special train.

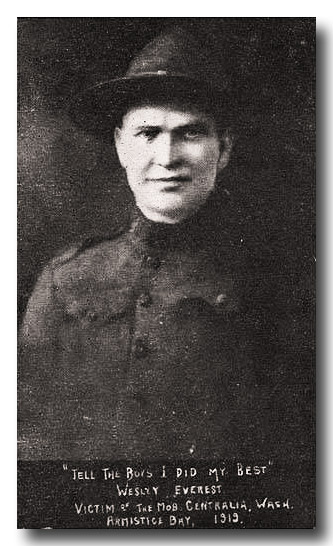

About seven that night several cars drove up near the jail with their lights out. Then, the lights of the city went out for about fifteen minutes and men entered the jail and removed Wesley Everest. Everest was placed in a car, followed by others and driven to a bridge spanning the Chehalis River about a mile away on the southwest side of town. He was hanged and shot. The body remained hanging for some time. Several cars drove out to view the sight. Later, someone cut the rope and the body drifted downstream and came to rest near the river’s edge.

The train with the National Guardsmen arrived at 11:35 pm. Gradually, the calls for more lynchings died down. The crowd was aware that the National Guard was in town and was beginning to set up checkpoints. The crowds gradually became smaller as the night wore on.

Was Wesley Everest emasculated in the vehicle which conveyed him to the bridge? McClelland, the leading authority on the incident, feels that it was not simply a story perpetuated by the IWW, since IWW members were in no position to do so in the days after the lynching. Years after the event, an affidavit was signed by a purported passenger in the car in which Everest was riding, which described the event in horrifying detail.

The corpse of Everest was retrieved and brought back to the small Centralia jail where it was placed in the corridor between the rows of cells.

Eventually, a group of prisoners were ordered to bury Everest in “Potter’s Field” while being watched over by National Guardsmen.

The jails of Centralia and Chehalis were full. Eventually, the following were charged with conspiracy to commit murder in the first degree: Eugene Barnett, Ray Becker, James McInerney, Britt Smith, Bert Bland, Loren Roberts, O.C. Bland, John Lamb, Mike Sheehan, and Bert Faulkner. Elmer Smith was charged as an accessory to the crime of conspiracy to commit first degree murder.

State labor officials knew that the trial would be used by some employers to beat down the long-established, more traditional craft unions. Thus, they decided to create their own “labor jury.” “These labor jury participants,” said McClelland, “were expected to be present at the trial, and to reach their own independent verdict.” There was some disagreement within the labor union movement. As McClelland pointed out, “The Seattle Central Labor Council expressed disapproval of the methods being used by the Centralia committee—especially when it sponsored picketing in Olympia—and accused it of capitalizing on the plight of the prisoners for private ends. The Seattle Federal Employees Union also announced it was ‘voting against the IWW.’”

Despite some opposition, Northwest labor leaders felt that the Wobblies, for all their irrationality, deserved a fair trail, and so they conceived the idea of sending a jury of their own, made up of working men, to sit through the trial and render a verdict at the same time the official verdict came in.

Even though most craft union leaders and members did not agree with the radical beliefs and actions of the IWW, they realized that their unions were, in a sense, “on trial” as well. They realized that anti-union employers would seize upon the radical actions of the IWW and use that as an example of the type of union activity that they claimed was typical. That is to say, they would attempt to tar the craft unions with the same brush they used to tar the IWW.

Some unions were eager to dissociate themselves from the IWW. The union which represented many employees of the Centralia Chronicle was quick to point out through a resolution that their members decried the methods used by the IWW. Unions in the Puget Sound area were aware that something would have to be done to counteract employers’ efforts to take advantage of the Centralia massacre and attempt to turn public opinion against the labor movement in general.

Those who were selected were John O. Craft, Metal Trades Council, Seattle; Paul Mohr, Central Labor Council, Seattle; W.J. Beard, Tacoma Labor Council; T. Meyer, Everett Labor Council; William Hickman, Portland Labor Council; and E.W. Thrall, Centralia Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen. “They took their assignment seriously, sitting through every session of the long trial,” according to McClelland.

The judge at the trial explained near the beginning that this was not a trial against the Industrial Workers of the World, it was a trial against certain individuals for conspiracy to commit first-degree murder. However, there was bound to be a great deal of discussion about labor unions during the course of the trial. The attorney for the defendants, George Vanderveer, argued, for example, “that industrial unionism was superior to craft unionism because a union representing all workers in an industry, such as steel, transportation, or lumber, was stronger than similar smaller AFL craft unions.” (McClelland points out that, “This was fourteen years before belated acceptance of the industrial union principle led to the formation of what became the Congress of Industrial Organizations.”)